We just finished day 9 since arriving in the study area. It is Saturday 12 December 2015. Today our focus was on the far south-western part of the study area between Bigge Island and the mainland (see map below). Because this area is poorly surveyed, we had to carefully multi-beam it first to ensure no shallow areas not marked on the nautical charts would surprise us.

Most of the sea floor that we’ve surveyed so far has been made mainly of mud. Some of it thick, sticky and stinky. And, though you may never have thought about it, mud is heavy.

To find out what is living in all that mud, we collect critters from the sea floor with the sled (see earlier blog about how we use sleds). Before we do that, we need to know what the sea floor is like. If the sea floor is mostly hard or likely contains large sponges or corals, then we need the AIMS sled because it has a larger opening and digs deeper into the sea floor. If the bottom is mostly soft mud, then the CSIRO sled works better because it is less likely to collect too much heavy mud.

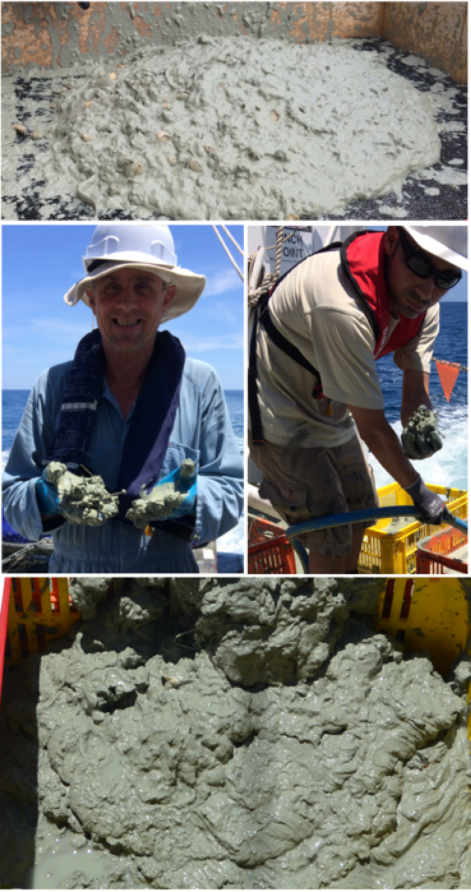

In fact, we got a surprise when we used the AIMS sled just south of Championet Island on the western side of Bigge Island on 6 December. The sea floor was muddier than we expected even though we checked with a grab sample first (I’ll explain how we do grab samples next). It was so muddy that the net of the AIMS sled was overflowing with mud to a height of at least 2 metres and a width of a metre (see below).

All that mud was so heavy, that after an hour of intense effort, the Solander crew were unable to lift the net on-board even using the Solander’s heavy duty crane. We had no choice but to empty the net back into the sea. I suspect that the Australian Museum scientists were secretly relieved because sorting through all the critters living in that massive blob of mud would have taken them a very, very long time!

How do we check what is on the sea floor?

We can do a quick check of what is on the sea floor in a given location by using a grab sampler (see below). We use the Smith and MacIntyre Grab

First, the skipper slows the boat to a stop. Then the crew use a winch to lower the Grab to the sea bottom. Once it hits bottom, its jaws open to grab a sample and then they spring shut. After the Grab is winched back on deck, scientists scoop out a sample for analysis. Watch out while the sample tray is emptied – SPLAT!

What lives in the mud?

The grab sample doesn’t tell us much about what creatures live on the sea floor. For that, we use a sled. Surprisingly, lots of creatures of many different types live happily in the mud. But it takes a dedicated team of scientists to search painstakingly through all the mud to find them (see below).

All that effort is worthwhile to discover the amazing array of creatures that make their home on the muddy sea floor. Below is a sampling of some of them, as photographed by John Keesing of CSIRO.

You have probably seen crustaceans before if you like to eat seafood. Crabs, prawns and bugs are all crustaceans, as are lobsters. Crustaceans usually have a skeleton outside their body (a hard shell that is part of their body) and two antenna to help them sense the world around them. Can you find the hard shells and antennae on the crustaceans below?

Sea stars normally have 5 arms, but some have more. If they lose an arm, it can grow back though it might take days to months. In the pictures below, you can see the underside of the sea star. Look closely to see its mouth.

Brittle stars are similar to sea stars, but with longer and more flexible arms. Usually they have 5 arms, which they use to crawl across the sea floor.

some gastropods live in shells which they carry around with them, just like a turtle. They do this to protect their soft bodies from being eaten. As they grow, they have to find new shells to move into. In the photos below, look closely to see the animal living inside (and poking out of) the shells.

Sea pens are named after the quills (feathers) that people used to write with in the 1800s by dipping them in ink. In the picture below, notice how the sea pen is long and thin with feathery bits on the end – just like a quill. A sea pen is actually made up of many polyps that work together to create a colony – just like in a coral. Unlike soft corals, sea pens like to attach themselves to the sea floor by digging into sand or mud.

- Fish

Many types of fish like to eat the small creatures that live in and on muddy sea floors. The lower picture is an Eel . Even though the eel looks like a snake, it is really a fish.

Sea cucumbers have long thick worm-like bodies with leathery skin. They have tentacles around their mouths, and a series of tube feet along their bodies. See if you can find the tentacles on the sea cucumbers in the photos below. Try to count how many tubed feet they have.

Examples of sea cucumbers we found living in the mud.

Soft corals are actually a group of many separate animals (polyps) that work together to form a colony. Hard corals make their own skeleton outside their bodies for protection. Soft corals also create protection for their bodies – but in the form of tiny, spiny elements called sclerities. So soft coral bodies remain flexible.

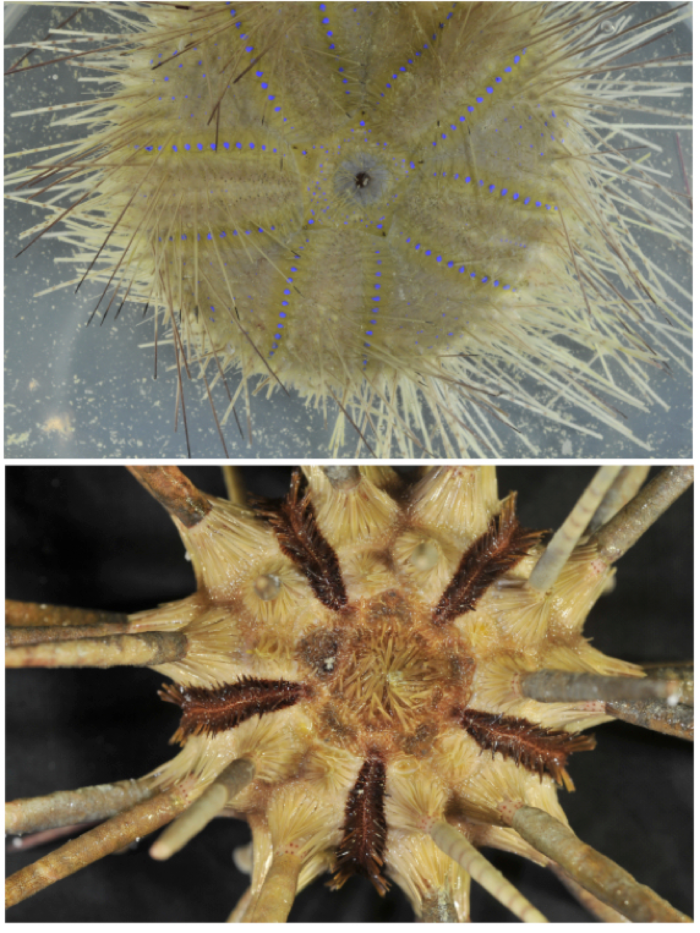

Sea urchins are small (usually 3 to 10 cm across), round animals covered with spines. Sea urchins like to eat algae. Lots of animals like to eat sea urchins, including sea otters, starfish, and some kinds of fish. Look at how different the spines look on the two sea urchins below.

Did you know…?

- A sea pen can grow up to 2 metres long.

- Many people in south-east Asia and China love to eat sea cucumbers. Some even use dried sea cucumber to make chocolate chip cookies!

- The largest brittle stars can have arms up to 60 cm long.

- Scientists are urging Australians to start eating sea urchins.

Why is the mud in our study area so stinky?

We are surveying the sea floor in relatively shallow waters (20 to 45 m deep). Lots of organic matter (dead bits of plants and animals) constantly lands on the sea floor. The bacteria that love to eat organic matter need to use oxygen dissolved in the water to be able to digest it. But they run out of dissolved oxygen before they run out of food. So they use different forms of oxygen that release sulfur – and make that very stinky rotten-egg smell. If we collected mud from very deep waters, the mud would not stink because the bacteria would be able to eat all the organic matter without running out of dissolved oxygen.

Thanks for reading – see you next time!